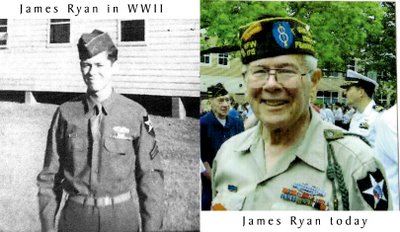

James A. Ryan

By Bob Staranowicz, BucksLocalNews.com Correspondent

“I would not swap the experience for anything, but I wouldn’t and I couldn’t repeat it.”

Born in Lancaster County, PA, Jim’s military service began with his enlistment in the Army Specialized Training Reserve Program in April of his senior year of high school.

Jim enlisted in the Army rather than waiting to be drafted because, as he reflected, “my Country needed me.” He was sent to Virginia Military Institute (VMI) and began his infantry training and was also enrolled in an engineering course. After a short leave, he was sent to the local induction center and shipped to Camp Croft, SC for basic infantry training in preparation for combat duty in Europe where he was assigned to the 8th Infantry Division, also known as the “Pathfinders.”

“Because of my training at VMI, I was promoted to the temporary rank of ‘Saltwater Sergeant’.” This was a temporary non-commissioned officer position that put Jim in charge of a unit during the Atlantic Crossing.

“While travelling from Boston on our troop ship, we were heading Southeast towards Bermuda but changed direction. We headed Northeast enroute to the English Channel.” This maneuver was a strategy used to fool any submarines that may have been tracking the ship.

The change in course was met by a storm and heavy seas and many were sickened by the movement of the sea. “After the storm, the sea turned to a beautiful blue and white. We approached the English Channel, but steered northward and rounded Ireland where we were met by two destroyer escort vessels. But, we were still attacked by two U-Boats that had been lying in wait on the bottom with their engines off. Depth charges were dropped and a Short Sunderland Flying Boat appeared and sprayed the area with tracer rounds.” The Flying Boat had its name taken from a town in northeast England; the Sunderland was one of the most powerful flying boats used in the Second World War. It was mainly involved in fending off threats by German U-boats in the Atlantic Theater Battles.

“After we arrived in Glasgow, we learned that one of the two submarines that attacked us had been sunk.”

“It was the Battle for the Rhineland where I had my closest call. After attempting to scale a wall and met with illumination from a powerful spotlight, I hit the dirt. I noticed that an 88mm shell had gone through the wall where my back had been. I saw a tank approach and it lowered its gun directly at me. I couldn’t get any closer to the ground. Fortunately, the shell missed me and penetrated the dirt under me blowing me about eight feet into the air. As the tank continued to fire, two other GIs and I were pinned down. We thought that the tank was going to run us down. When we thought we had breathed our last, the US artillery intervened and the tank retreated. I was wounded but not severely enough to be separated from my unit.”

“We were one of the first regular infantry units to return from Europe and were slated for the Pacific Theater, most likely for the invasion of Japan.” While awaiting those orders, Jim had returned to the US at Norfolk, very happy to be back on American soil. Luckily, Jim did not have to make that trip to Japan, the dropping of the Atomic bomb prompted the surrender of Japan and the war was all but over.Jim continued his service as a platoon sergeant before his discharge.

After leaving the service, he attended various area schools, thanks to the GI Bill, before receiving his BS and MS in Chemistry from Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, PA. Jim’s dad, James Francis Ryan, was also a veteran and was wounded while serving as an ambulance driver in World War I during the Meuse Argonne Offensive – probably the greatest American battle in the First World War.Jim worked for several pharmaceutical companies as a research chemist before retiring from Merck in 1994.

Jim currently lives in Doylestown with his wife, Helen. The Ryans have four children and 12 grandchildren.

Jim is still active in veteran’s issues and is a member of American Legion Post 210 and the Doylestown VFW Post 175.

Labels: Army, Camp Croft, Doylestown, Virginia Military Institute, WWII

RSS Feeds

RSS Feeds