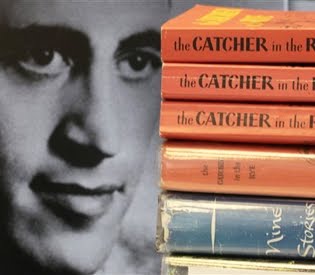

Holden Caulfield stays mum for now

Did J.D. Salinger write a novel - or 10 - to rival "The Catcher in the Rye"?

Did J.D. Salinger write a novel - or 10 - to rival "The Catcher in the Rye"?Below, The Assocated Press asks the question that's foremost on the fan's minds.

"What’s in J.D. Salinger’s safe?"

The death this week of J.D. Salinger ends one of literature’s most mysterious lives and intensifies one of its greatest mysteries: Was the author of "The Catcher in the Rye" keeping a stack of finished, unpublished manuscripts in a safe in his house in Cornish, New Hampshire? Are they masterpieces, curiosities or random scribbles?

No comment, says his literary representative, Phyllis Westberg, of Harold Ober Associates Inc.

Marcia B. Paul, an attorney for Salinger when the author sued last year to stop publication of a "Catcher" sequel, would not get on the phone Thursday.

Stories about a possible Salinger trove have been around for a long time. In 1999, New Hampshire neighbor Jerry Burt said the author had told him years earlier that he had written at least 15 unpublished books kept locked in a safe at his home. A year earlier, author and former Salinger girlfriend Joyce Maynard had written that Salinger used to write daily and had at least two novels stored away.

Salinger, who died Wednesday at age 91, began publishing short stories in the 1940s and became a sensation in the 1950s after the release of "Catcher," a novel that helped drive the already wary author into near-total seclusion. His last book, "Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour," came out in 1963 and his last published work of any kind, the short story "Hapworth 16, 1924," appeared in The New Yorker in 1965.

"I think there’s probably a lot in there, but I’m not sure if it’s necessarily what we hope it is," McInerney said Thursday. "’Hapworth’ was not a traditional or terribly satisfying work of fiction. It was an insane epistolary monologue, virtually shapeless and formless. I have a feeling that his later work is in that vein."

Author-editor Gordon Lish, who in the 1970s wrote an anonymous story that convinced some readers it was a Salinger original, said he was "certain" that good work was locked up in New Hampshire.

"I can’t wait to find out!" she said. "In our age of shameless self-promotion, it’s extraordinary, and kind of great, to think of someone really and truly writing for writing’s sake."

Some of the great works of literature have been published after the author’s death, and even against the author’s will, including such Franz Kafka novels as "The Trial" and "The Castle," which Kafka had requested be destroyed.

"There is a marvelous peace in not publishing," J.D. Salinger told The New York Times in 1974. "Publishing is a terrible invasion of my privacy. I like to write. I love to write. But I write just for myself and my own pleasure."

Labels: J.D. Salinger

RSS

RSS